by Benjamin Roberts, Jare Struwig, Narnia Bohler-Muller, and Steven Gordon

Powerful new technologies are emerging that will continue to affect individuals in multiple ways. This has led to references to a Fourth Industrial Revolution – a new era involving the application of digitisation and automation to different areas of society and everyday life. This revolution is one that presents distinct opportunity. But it also presents major risk and human costs.

These changes have become a growing point of discussion in most countries in the world. In South Africa the debate has drawn in policymakers, business and unions. But the voices of average South Africans have been missing from the debate. A survey completed earlier this year by the Human Sciences Research Council contributes to addressing this gap.

Consisting of 2,736 respondents older than 15, the results suggest the public recognises the promise – and the pitfalls – of this technological turn. Most people have a moderately positive view of digital technologies, but they are sceptical about the impact it will have on the labour market.

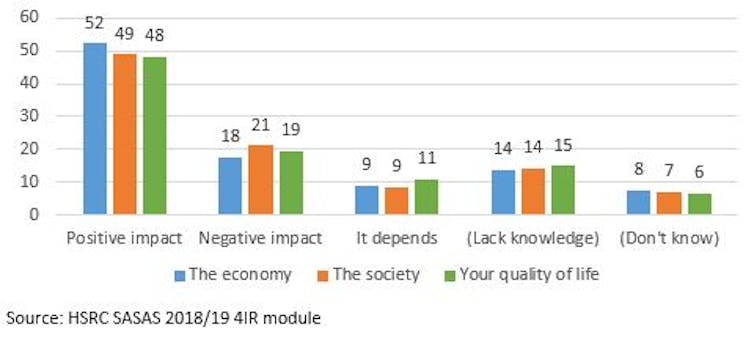

Those who took part in the survey appeared cautiously optimistic when asked about the potential impact of recent computer and internet technologies on the economy, society, and personal quality of life.

HSRC SASAS 2018/19 4IR module

Around half – 48% – 52% – believed that the advances would be beneficial economically, societally and personally. A fifth expressed reservations, with the employed specifically concerned about job losses. They tended to acknowledge that automation would have a bearing on the workplace. A sizeable majority were concerned that it will affect them.

Public opinion remains critical from a policy and accountability perspective, as the priorities deemed important by citizens should be used to inform government’s agenda. Concerns about possible job loss due to technological change need to be considered in developing social protection and other measures to minimise the negative effects. Ignoring peoples’ voices could have far-reaching political consequences.

The threat

Three-quarters (73%) of South Africans believed that in the next decade machines or computer programmes would assume many of the jobs presently done by humans. In addition, six in 10 workers (62%) were very or quite worried that such automation will threaten their job security.

Compared to the UK, South Africans exhibited almost equivalent views on the likelihood of automation impacting on the labour market (73% versus 75%). But local workers demonstrated vastly higher levels of worry about the personal job impact of automation than is evident among British workers (62% vs. 10%).

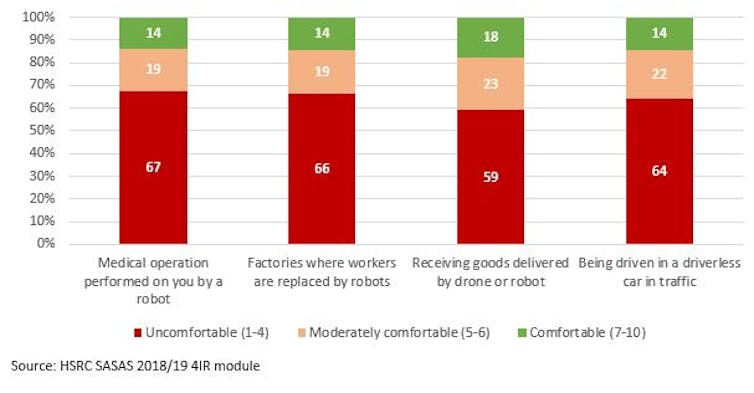

To gauge how culturally accepting South Africans are of technological change, respondents were asked to rate how comfortable they felt with four situations involving the use of robots:

(i) a medical operation performed by a robot;

(ii) factories where workers are replaced by robots;

(iii) receiving goods delivered by drone or robot; and

(iv) being driven in a driverless car or taxi in traffic.

They provided scores using a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means ‘totally uncomfortable’ and 10 ‘totally comfortable’ (Fig. 2).

HSRC SASAS 2018/19 4IR module

On average, respondents weren’t particularly accepting of any of these four scenarios. Only 14-18% expressed comfort, 19-23% would be moderately comfortable, while 59-67% were uncomfortable with such propositions.

Government’s capability

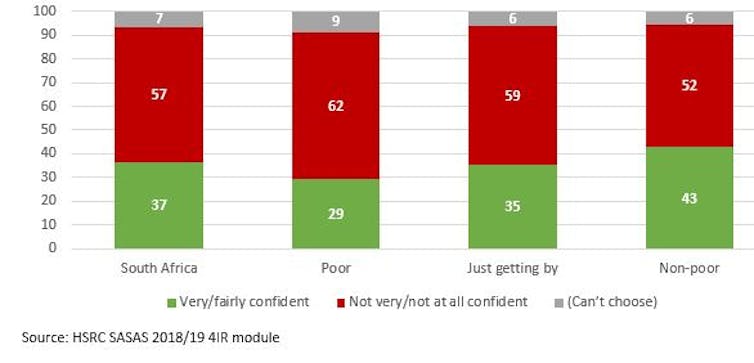

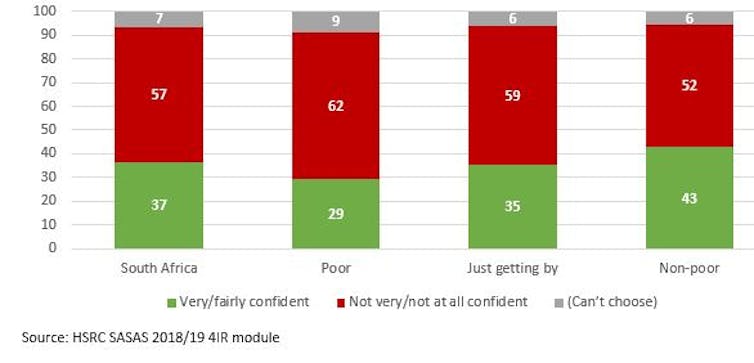

We also set out to establish how confident people were in the government’s ability to intervene successfully to minimise adverse affects on the labour market.

Little more than a third (37%) were very or fairly confident that government could effectively put in place strategies to ensure that new technologies do not result in job losses, while 57% were doubtful (Fig 3). Poorer South Africans expressed greater scepticism than better off South Africans. While the survey results didn’t address the role to be played by other role-players (especially market actors), it nonetheless provided a sense of views on state policy to address any adverse labour impact that automation might produce.

HSRC SASAS 2018/19 4IR module

What next?

The analysis suggests that, generally, there’s more optimism than circumspection about the impact of the newest digital technologies on society and peoples’ general well being. But, there’s recognition that automation will affect the labour market and there are deep concerns exist over the threat this poses to jobs. There is also broad discomfort with robots performing a range of tasks. This points to quite low levels of cultural acceptance of the application of robots.

If technological change creates further labour market inequality and sustained reductions in human employment, then carefully planned social and labour market policies will be required to address low pay, precarious employment, and expanded, long-term unemployment.

At this stage, the public is fairly pessimistic about the ability of government to minimise the human costs of the fourth industrial revolution. Ongoing dialogue between various sectors, such as at the recent inaugural Fourth Industrial Revolution SA Digital Economy Summit in South Africa, are needed to promote new insights and develop responses. There should also be campaigns to inform the public about technological change and the planned response for the country.![]()

![]()

Benjamin Roberts, Chief Research Specialist and Coordinator of the South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS), Human Sciences Research Council; Jare Struwig, Chief Research Manager, Human Sciences Research Council; Narnia Bohler-Muller, Executive Director of the Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery Programme at the Human Sciences Research Council and Adjunct professor of law, University of Fort Hare, and Steven Gordon, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Human Sciences Research Council

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.