by Eric Zeng, Carnegie Mellon University

The European Union filed an antitrust case against Google on June 14, 2023, charging that the company abused its power in the online advertising market to disadvantage its competition. The U.S. Department of Justice filed a similar civil antitrust suit against Google on Jan. 24, 2023.

The online ad ecosystem is largely built around “programmatic advertising,” a system for placing advertisements from millions of advertisers on millions of websites. The system uses computers to automate bidding by advertisers on available ad spaces, often with transactions occurring faster than would be possible manually. Google runs the dominant advertising platform and has 28% market share of global advertising revenue.

Most websites outsource the task of selling ads to a complex network of advertising tech companies that do the work of figuring out which ads are shown to each particular person. Programmatic advertising is also a powerful tool that allows advertisers to target and reach people on a huge range of websites.

As a postdoctoral researcher in computer science, I study these technologies and companies, including how sketchy ads, like those for miracle weight-loss pills and suspicious-looking software, sometimes appear on legitimate, well-regarded websites.

Programmatic advertising, explained

The modern online advertising marketplace is meant to solve one problem: match the high volume of advertisements with the large number of ad spaces. The websites want to keep their ad spaces full and at the best prices, and the advertisers want to target their ads to relevant sites and users.

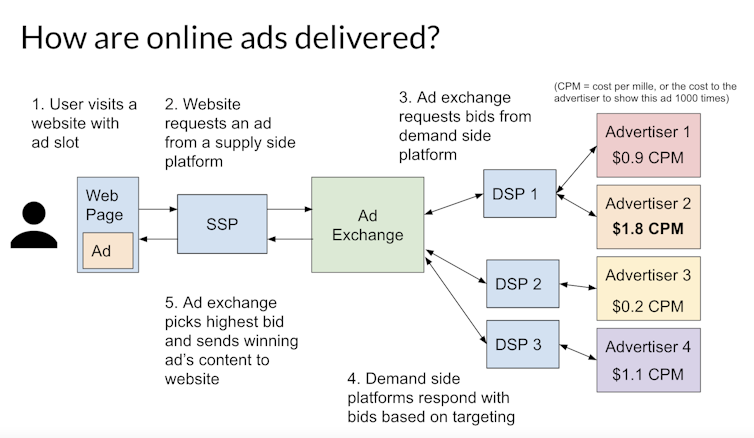

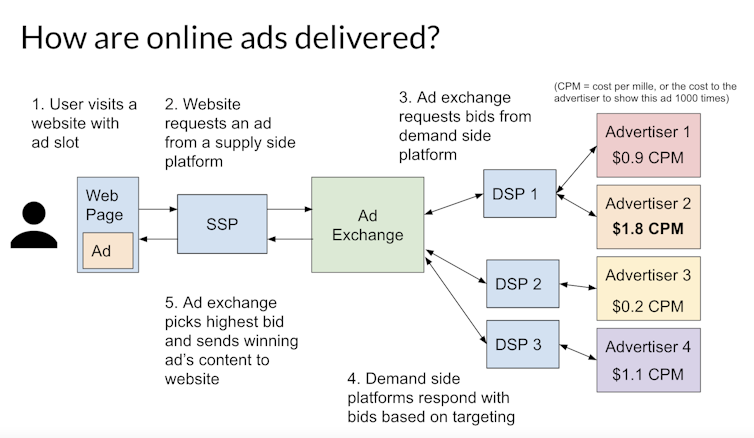

Rather than each website and advertiser pairing up to run ads together, advertisers work with demand-side platforms – tech companies that let advertisers buy ads. Websites work with supply-side platforms – tech companies that pay sites to put ads on their page. These companies handle the details of figuring out which websites and users should be matched with specific ads.

Most of the time, ad tech companies decide which ads to show through a real-time bidding auction. Whenever a person loads a website, and the website has a space for an ad, the website’s supply-side platform will request bids for ads from demand-side platforms through an auction system called an ad exchange. The demand-side platform will decide which ad in their inventory best targets the particular user, based on any information they’ve collected about the user’s interests and web history from tracking users’ browsing, and then submit a bid. The winner of this auction gets to place their ad in front of the user. This all happens in an instant.

Eric Zeng, CC BY-ND

Google runs a supply-side platform, demand-side platform and an exchange. These three components make up an ad network. Google’s control of these three components sets the stage for the company to manipulate the market, as the EU and Justice Department allege the company has done. A variety of smaller companies such as Criteo, Pubmatic, Rubicon and AppNexus also operate in the online advertising market.

This system allows an advertiser to run ads to potentially millions of users, across millions of websites, without needing to know the details of how that happens. And it allows websites to solicit ads from countless potential advertisers without needing to contact or reach an agreement with any of them.

Screening out bad ads

Malicious advertisers, like any other advertiser, can take advantage of the scale and reach of programmatic advertising to send scams and links to malware to potentially millions of users on any website. I study how malicious online advertisers take advantage of this system. This means that online advertising companies have a big responsibility to prevent harmful ads from reaching users, but they sometimes fall short.

There are some checks against bad ads at multiple levels. Ad networks, supply-side platforms and demand-side platforms typically have content policies restricting harmful ads. For example, Google Ads has an extensive content policy that forbids illegal and dangerous products, inappropriate and offensive content, and a long list of deceptive techniques, such as phishing, clickbait, false advertising and doctored imagery.

However, other ad networks have less stringent policies. For example, MGID, a native advertising network my colleagues and I examined for a study and found to run many lower-quality ads, has a much shorter content policy that prohibits illegal, offensive and malicious ads, and a single line about “misleading, inaccurate or deceitful information.” Native advertising is designed to imitate the look and feel of the website that it appears on, and is typically responsible for the sketchy looking ads at the bottom of news articles. Another native ad network, content.ad, has no content policy on their website at all.

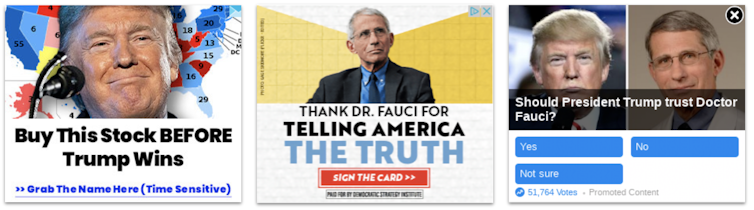

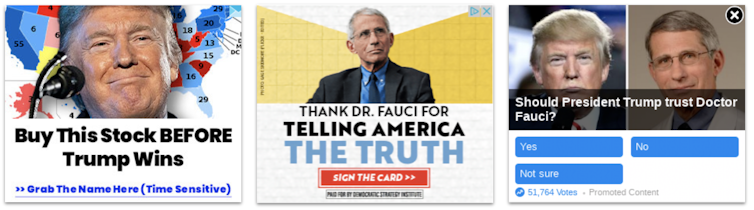

Screenshots by Eric Zeng

Websites can block specific advertisers and categories of ads. For example, a site could block a particular advertiser that has been running scammy ads on their page, or specific ad networks that have been serving low-quality ads.

However, these policies are only as good as the enforcement. Ad networks typically use a combination of manual content moderators and automated tools to check that each ad campaign complies with their policies. How effective these are is unclear, but a report by Confiant, a firm that tracks malware in advertising, suggests that between 0.14% and 1.29% of ads served by various supply-side platforms in the third quarter of 2020 were low quality.

Malicious advertisers adapt to countermeasures and figure out ways to evade automated or manual auditing of their ads, or exploit gray areas in content policies. For example, in a study my colleagues and I conducted on deceptive political ads during the 2020 U.S. elections, we found many examples of fake political polls, which purported to be public opinion polls but asked for an email address to vote. Voting in the poll signed the user up for political email lists. Despite this deception, ads like these may not have violated Google’s content policies for political content, data collection or misrepresentation, or were simply missed in the review process.

Bad ads by design

Lastly, some examples of “bad” ads are intentionally designed to be misleading and deceptive, by both the website and ad network. Native ads are a prime example. They apparently are effective because native advertising companies claim higher clickthrough rates and revenue for sites. Studies have shown that this is likely because users have difficulty telling the difference between native ads and the website’s content.

Screenshot by Eric Zeng

You may have seen native ads on many news and media websites, including on major sites like CNN, USA Today and Vox. If you scroll to the bottom of a news article, there may be a section called “sponsored content” or “around the web,” containing what look like news articles. However, all of these are paid content. My colleagues and I conducted a study on native advertising on news and misinformation websites and found that these native ads disproportionately contained potentially deceptive and misleading content, such as ads for unregulated health supplements, deceptively written advertorials, investment pitches and material from content farms.

This highlights an unfortunate situation. Even reputable news and media websites are struggling to earn revenue, and turn to running deceptive and misleading ads on their sites to earn more income, despite the risks it poses to their users and the cost to their reputations.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on April 13, 2022.![]()

![]()

Eric Zeng, Postdoctoral Researcher in Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.