By James Stent

On Wednesday, the Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ) leaked discussion documents from the Presidency and the National Treasury. The IEJ criticised the documents for dismissing a Universal Basic Income Grant and for suggesting replacing the R350 Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant with conditional grant measures.

The two documents – July’s Putting South Africa to Work from the Presidency and the National Treasury’s August response to this paper – suggest that the government wants to pursue a system that would make grants conditional on actively seeking employment or on being the primary caregiver, rather than a universal basic income grant (UBIG).

These discussion documents provide crucial insight into the deliberative processes within the Presidency and the National Treasury. Interestingly, the Treasury appears to be adopting a position that runs against the preferences of the ANC’s most recent policy release, and the Department of Social Development.

Here, in a nutshell, is what the two documents say.

South Africa’s crises of unemployment, poverty and inequality

Both documents describe South Africa being in a difficult state. The National Treasury describes South Africa as being “on a path to a fiscal crisis” without more growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or tax revenue. In the Presidency’s document, this is particularly centred around our intractable unemployment crisis. A “structural break” is needed.

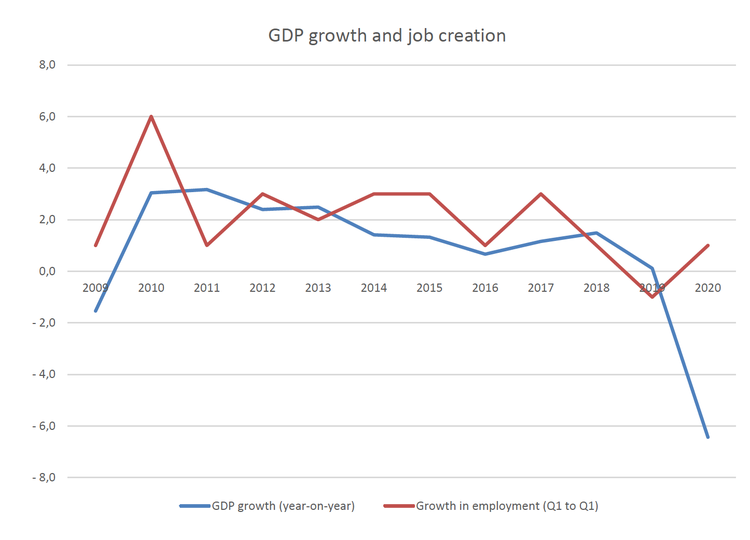

The economy never managed to recover from the impact of the global financial crisis, and the economic performance during the Jacob Zuma presidency was characterised by flat GDP growth and joblessness remaining devastatingly high.

The type of public spending preferred during Zuma’s presidency was mostly geared towards state owned companies and permanent public employment. This was ineffective and largely funded by debt.

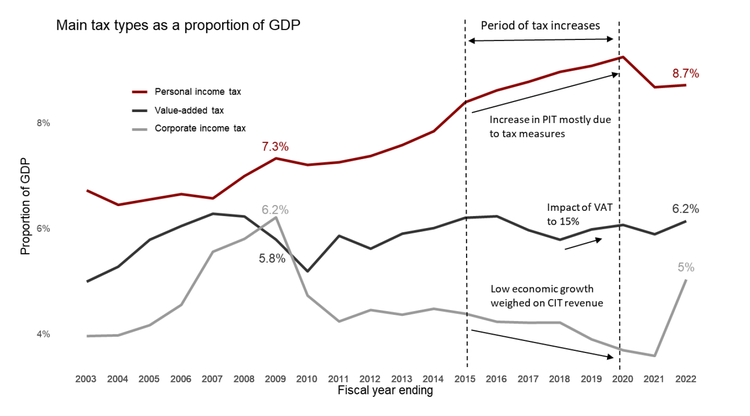

Tax increases from 2015 did not raise revenues as was hoped; this also coincided with “institutional problems” at the South African Revenue Service that may have played a large role in reduced revenue.

A fifth of households do not earn enough to keep themselves fed each month. Most youth have never had a job and are not engaged in getting skills. The economy is dominated by large firms that crowd out smaller companies, and small business and self-employment is far lower than similar countries.

In order to prevent the “fiscal crisis”, South Africa needs job-rich economic growth. These jobs must be good – that contribute productively. This is difficult, because there are not a lot of labour-focused jobs available.

The Social Relief of Distress (SRD) grant keeps people alive. More than half of its recipients have never been formally employed.

As things stand, South Africa’s economy is growing more slowly than our debt burden. Public bonds are not selling to expectations. There is a lot of scepticism within the National Treasury about South Africa’s ability to take on new debt.

But despite the difficult environment, the Presidency sees that there is consensus and urgency in society to finally act.

How does the Presidency want to put South Africa to work

The Presidency considers four themes of intervention.

- Radically increase private sector employment. This means “addressing the energy shortfall”, making life easier for smaller businesses to employ people, and promoting labour-intensive industries.

- Increase publicly-funded employment. This would further fund and improve projects like the Expanded Public Works Programme, prioritising skills development.

- “Expand” social protection. This means introducing new grants programmes.

- “Support to enable productive livelihoods”. This would include support programmes to unemployed and poor people, like skills development and microfinance.

The Presidency’s document acknowledges contemporary research by Timothy Köhler and Haroon Bhorat on the impact of grants which shows that recipients of the SRD grant were 25% more likely to look for work than those who did not receive the grant, and other research that found that the grants reduced child hunger and led to reduced dropout rates.

With employment as its focus, the Presidency also wants to link social protection – such as the successor to the SRD grant – to jobs.

The Presidency’s report leans on an analysis conducted by the World Bank which “disaggregates the poor and unemployed”. This is a categorisation of people that currently receive the SRD grant.

This analysis divides the 10.6 million people that receive the SRD grant (this presumably describes the situation before March 2022) into three broad categories:

- The extremely poor, who are below the food poverty line and cannot work. This accounts for 4.6-million people.

- The poor, who may, with assistance, work if jobs were available. This accounts for 4.1-million people.

- The “less poor”, who are ready to work, if jobs were available, who number 1.9-million people.

This graph shows changes in GDP and job growth since 2009. Source: Putting South Africa to Work (Presidency)

What are the options after the SRD grant?

The Presidency proposes four options:

- Continue with the SRD grant;

- Replace the SRD Grant with a Jobseekers Grant of similar value;

- Implement a Jobseekers Grant as well as a Caregivers Grant; and,

- Implement a Minimum Income Guarantee to combine all interventions.

The costs of these options are examined under two conditions – the grants remain at R350, or are adjusted to meet the food poverty line (currently R624 per month) – and jobs through a public programme like the Presidential Employment Programmes (PEPs) are also evaluated.

The SRD extension would reach 9.8-million people. One million would receive PEP jobs. The cost, for 2023/24, would be R64-billion at the current amount of R350, and R94-billion at the R624 food poverty line.

The Jobseekers grant alone would reach over 8-million people. 750,000 would receive PEP jobs. The cost, for 2023/24, would be R52-billion at R350, and R78-billion at the food poverty line. Fewer people would receive this grant, as targeting would be used to include a spouse’s income in the approval threshold.

The Jobseekers and Caregivers grants would also reach over 8-million people. One million people would receive PEP jobs. The cost would be R57-billion at R350, and R82-billion at the food poverty line for 2023/24.

The Minimum Income Guarantee would reach 10-million people. 750,000 would receive PEP jobs. The cost would be R59-billion at R350, and R90-billion at the food poverty line for 2023/24.

The Jobseekers grant would work like this: Recipients would need to be registered on a jobs database. They must be available to work, and, if a job was offered, have to accept that job. They would be offered skills training. If they were between 18 and 24 and had not completed matric, they would need to be working towards that.

A Caregivers grant would be given to unemployed caregivers – people looking after children. The requirement for this grant would be that all children under the age of 18 would have to be enrolled in school.

The SRD grant would have the lowest administrative burden – it would be given to any person with income below the food poverty line. The other options would require the establishment of new databases, labour support bureaux, and other systems.

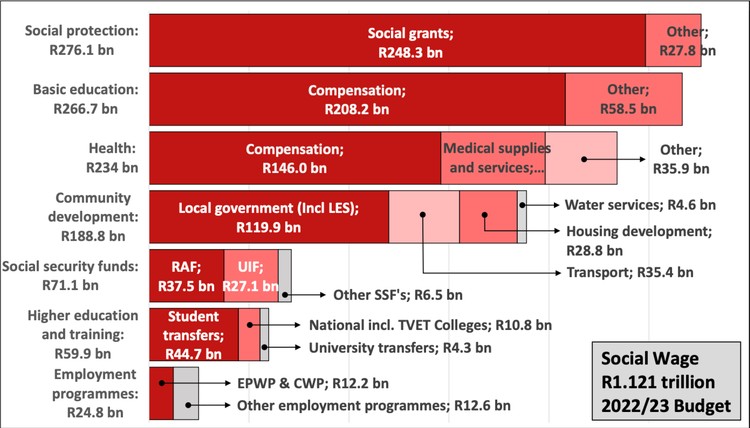

How the “social wage” part of the budget is made up in the current financial year. Source: Future of the R350 Grant (National Treasury)

Why does the National Treasury want a targeted grants programme?

The National Treasury considers the introduction of the Jobseekers and Caregivers grant (option 3) “an acceptable compromise”.

The worry, for the National Treasury, is that funding an untargeted grant is beyond South Africa’s capacity, and that the number of people who would qualify for the SRD grant is “heading to 16-18-million people”. They use the World Bank’s analysis to suggest that there is a large number of SRD recipients who do not need the grant.The National Treasury also expresses concern that the SRD grant may “supplant efforts to address constraints that continue to entrench exclusion from labour market”, which seems to mean that they believe that if people get grants they won’t get a job.

Why not raise taxes?

According to the National Treasury, the least expensive option of those presented by the Presidency for the grants regime that would replace the R350 SRD would cost at least R50-billion.

The National Treasury’s document considers the options for raising this amount: including whether it would be possible to raise personal income tax and value added tax (VAT), and if a ‘solidarity tax’ would be effective.

It rules out a once-off solidarity tax as a way to finance new grants, as this would only account for the grants over the short-term.

Increasing personal income tax for the wealthiest is is not favoured. The Treasury argues it may be “counterproductive” as previous tax rate increases did not lead to increased tax revenue. However, lowering the tax-free threshold is seen as a viable option. The Treasury offer a scenario in which R50-billion is raised by reducing the tax-free threshold to R75,000 per year, and raising income tax levels across the board by 1.5%.

Raising the corporate income tax level is barely contemplated – Treasury argues it would be “detrimental”.

Treasury also considers raising VAT. VAT is a regressive tax – meaning that it affects poor people more than wealthier people – unless poor people are compensated by social grants. Treasury considers four scenarios, and finds that options which increase VAT to 16%, or which keep VAT stable but remove some zero-rated items, led to better outcomes.

Treasury also looked at ‘external’ tax proposals. A direct wealth tax is considered, in line with the recommendations of the Davis Tax Committee, and research by Aroop Chatterjee, Léo Czajka and Amory Gethin. But Treasury’s opinion seems to be that this would be too difficult to implement, as it would require knowing who owns what in South Africa.

The IEJ’s Basic Income Guarantee proposals are considered briefly And proposals like removing tax breaks for the retirement savings of the highest earners (which could net R18-billion by the Treasury’s own calculation) are dismissed as “difficult”.

How the different types of tax compare in size. Source: Future of the R350 Grant (National Treasury)

What about moving money around?

The message of their document is clear: National Treasury will not spend more than it currently does to fund the SRD or its replacement. Without increased revenues from tax, which would only occur if the plans to increase GDP growth work, there cannot be more government spending.

To this end, the Treasury identifies R21-billion in government programmes and current expenditure that could be shut down or suspended.

The Passenger Rail Agency of SA (PRASA) is targeted – the National Treasury says it is “not fit for purpose and runs large unfunded operational deficits.” It seems to support the devolution of commuter rail to municipalities.

Long-distance trains (like the Cape Town to Johannesburg Shosholoza Meyl) and the bus service Autopax would be cut off (saving R1.4-billion), and R12.8 billion in capital projects (which would include fixing the devastated rail lines or the Water Services Infrastructure Grant) would be suspended. SANRAL’s road building programme would also be suspended, and we would end our peacekeeping mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, both saving R2.4-billion.

These would be short-term measures. In the medium-term, government departments and programmes would be “rationalised”; reductions, mergers, and retrenchments would follow.